Collective Power: Western Esotericism and Design

In his work, "The Castle of Crossed Destinies, ” Italo Calvino famously said, “The tarot is a machine for constructing stories.” Calvino’s sentiment encapsulates this story, a narrative recounting women who challenged dominant social systems in spiritualism and design. Our subjects include pioneering women in Western esotericism and tarot card designers Edith "Ditha" Moser (1883–1969), Pamela Colman Smith (1878–1951), and Frieda Harris (1877–1962), among others. Often overlooked in design history is work that was produced for spiritual purposes. These entrepreneurial women’s work shaped present-day divination practices and the origins of contemporary tarot cards.This critical history foregrounds several conditions. Considering the convergence of spiritualism and design highlights a crucial moment when women pursued alternative avenues to do their work. A pattern of subversion can be found in countless examples. In design and spiritual practice, women could circumvent social customs to assert their agenda in both public and private domains. Histories like this provide opportunities to reflect on the extent and nature of women working in design during this period, which were often novel because women worked under constraints not present to their male counterparts.

The constraints mentioned are not reflected in historiographic methods. Design history’s prevailing praxis involves the “selection, classification, and prioritization of types of design, categories of designers, distinct styles and movements, and different modes of production” (Buckley 3). Buckley continues that these methods are inherently biased against women and, in effect, exclude them from history. Showcasing single-male involvement over women's collaborative work narrows the definition of what design is or is not, precludes contexts outside what is “normal,” and fails to tell stories of women working on the margins.

Collecting and presenting this data helps us understand the influences on current practice. Tarot is among the gamut of Western esoteric practices that have seen a mainstream resurgence in recent years, along with astrology, psychics, reincarnation, and even witchcraft. In 2018, the Pew Research Centre found that six in ten Americans (both with religious affiliations and not) held at least one new-age belief, specifically psychics, the belief that spiritual energy can be found in physical objects, and astrology (Gecewicz). Highlighting the idiosyncratic work of these designers deserves attention, and their unconventional histories can teach us about today’s culture.

Social Change & Western Esotericism

Our story begins primarily in the 19th century, a time of social upheavals and rapid industrialization. It can be characterized as a century of change; the first Industrial Revolution remade economies by displacing the agrarian with a manufacturing economy. Products were no longer made by hand but by machines, which increased production efficiency and improved wages. The Second Industrial Revolution led to massive urbanization, enabling people to work in the same factories. Essential social reform movements, such as abolition and women's suffrage, abolished slavery, improved social conditions, and granted some political empowerment and equality. Women’s rights campaigns paved the way for increased educational opportunities. “During the second half of the 19th century, many art and design schools opened throughout the country, and many of them accepted women students” (Thomson 31). New York School of Applied Design for Women, 1892, or the Philadelphia School of Design, 1848, focused on vocational training to provide women with employment opportunities. “Professional training for careers in the arts offered a way to evade the confines of domesticity while retaining the appearance of gentility associated with unpaid work in the home” (Wall 330). The importance of these institutions is foundational to the three women in this story and to women’s involvement in design.

At the same time, Western esotericism, a loose category of religious movements that combine philosophy, mysticism, and religion with scientific discourses, art, and literature, flourished as a space that upended gender assumptions. Though the category of Western esoteric practices is a modern scholarly construct, the parallels these movements share are a hidden inner tradition, an embrace of the “enchanted” worldview in the face of disenchantment, and the seizure of Western cultures’ “rejected knowledge.” Women capitalized on these perspectives, granting themselves professional and social latitude in a restricted culture. They found acclamation in becoming leaders, community building, writing, and publishing. Moreover, those involved in these movements “began to speak out in public in sizable numbers” (Asprem 27). Many practices held non-conventional ideas opposing patriarchal notions of women's culpability as originators of sin. “Both state and traditional ecclesiastical institutions emphasized women's physical and mental inferiority, denied or limited their access to education, and barred them from positions in church, state, and professions because their roles as wives and mothers restricted them to the private sphere” (Asprem 71). Women could claim power and ownership over life in contrast to the dominant conventions in this space. “In this terrain, women imagined an alternative social environment and enacted that alternative world, which leveled the playing field” (Albanse 233).

Women of this era were innovative and created idiosyncratic spiritual practices or careers. They became community leaders and writers, illustrators, designers, and decorators. Financial gains were also necessary for the growing middle and upper-middle classes. Moreover, the home often became a site of work for women because it was considered appropriate and non-threatening to male sensibilities (Goodman 14). The context and value system of patriarchy constructed women’s roles, as the design historian Martha Scotford noted in her influential article, “Messy History vs. Neat History” (Scotford). This is also true for the Shakers, who, to a large extent, precipitated women’s leadership in Western esoteric movements. The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, commonly known as the Shakers, was a Protestant sect founded in England and later led by Ann Lee in the United States in 1776. For this group, Mother Ann Lee was the female manifestation of the divine presence advancing a feminist foundation within the community. Women held governance roles and were in the majority. Within the Shakers, there were more female “instruments.” An “instrument” channels messages from heavenly spirits through dance, speaking in tongues, and drawing. This was reasonable to those who believe “Mother Ann was a female second coming of Christ, yet for the group’s men, writes Stephen Stein, they were “provoked,” manifesting a latent hostility” (Albanse 234). Nevertheless, the group still practiced traditional gender roles, and women struggled to obtain and wield power. Anthropologist I.M Lewis found “that in women’s 'possession cults,' such as the Shakers, there were thinly veiled protest movements, directed at the dominant sex” (Albanse 234).

Additional organizations endeavored to improve social conditions for women. Transcendentalism developed in New England in the 1820s, with many women members. It was an early philosophical movement in the United States that saw religious experience in everyday life. Sarah Margaret Fuller (1810–1850) was an influential member who advocated for women’s rights among her contemporaries. This was also true for the Spiritualist movement—an occult practice in which clairvoyants channel messages from spirits—that saw a profusion of women spiritualists around 1848 and continues to this day. Spiritualists could operate in their homes, the conventional domain of women in this era. The practice provided them with social capital, economic movement, and the opportunity to promote social reform. Victoria Woodhull (1838–1937) was a recognized clairvoyant, a passionate lecturer, and an author on free love, owned a stock brokerage firm, and ran as a candidate for U.S. President in 1872. Spiritualists were not the only ones to criticize the prevailing limits on women’s freedom, although they were among the most radical.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) and Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) recognized the Spiritualists’ important role in the women’s movement. “The only religious sect in the world … that has recognized the equality of women is the Spiritualists” (Bressler 93). Autonomy also came simply from the practice itself, in the ability to channel the dead. For designers, self-actualization was afforded through their capacities and employment. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton hired Augusta Lewis Troup (1848–1920), an American printer, to create “Revolution,” a suffragist publication. Troup also established the Women Typographic Union No. 1, advocating for equal pay and better working conditions for women in the field. Hilda Dallas (1878–1958), an English Graphic Designer and Illustrator, designed posters for the Suffragette Atelier, which trained and supported artists to create media in favor of women’s suffrage.

Concurrently, the spiritualist movement, Theosophy, allied itself with other forces working for social and religious liberation, including suffragettes. Theosophy emerged from Spiritualism and was founded in New York City in 1875 by Russian Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) and American Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907). The practice combines several philosophies, including Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu thought, with the belief that God may be attained through spiritual ecstasy, direct intuition, or unique individual relationships. By 1889, the Theosophical Society had 227 sections worldwide and could list the era’s most influential intellectuals and artists among its members, including Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, William Butler Yeats, and Thomas Edison. Western esoteric movements and women in design contributed to the broader cultural shift toward women’s rights and gender equality. They created spaces that encouraged education and employment, or images that challenged gender stereotypes, shaping public perceptions and paving the way for greater societal equality.

Tarot Decks and Designers

The following designers, Edith “Ditha” Moser, Pamela Colman Smith, and Lady Frieda Harris, were all born in the latter half of the 19th century and created three distinct sets of tarot cards influenced by the ideas and currents of this era. It is important to note that tarot decks began as playing cards in the mid-15th century in northern Italy, spreading across Europe as the printing press made reproduction more viable. There were no established references to using tarot as a fortune-telling or divination tool—seeking insights and guidance about the past, present, or future—until the middle of the eighteenth century (Sosteric 361). Subsequent to that transition, they were enfolded into the occult lodges, secret societies, and other esoteric systems that became extremely popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries (Ross). Each deck comprises 78 cards divided into the Major Arcana (22 cards) and the Minor Arcana (56 cards). Tarot decks draw on Hermetic and Kabbalistic teachings, paralleling the practitioner's spiritual journey with the Tree of Life in Kabbalah, with its ten spheres. Decks also incorporate astrological and elemental correspondences. These associations align with Western esoteric traditions that emphasize the interplay between divine forces and human experience, resonating with practicing individuals.

In 1906, Edith Moser, an Austrian Graphic Designer and member of the Vienna Secession, created the Jugendstil Tarot deck. Moser was also part of the Wiener Werkstätte that her husband, Solomon Moser, helped found in 1903. Both groups included members of the Theosophical Society. Regarded as a pioneer of modernist design, the workshop sought to effect reform across fields, from architecture and interior design to textiles and book design.

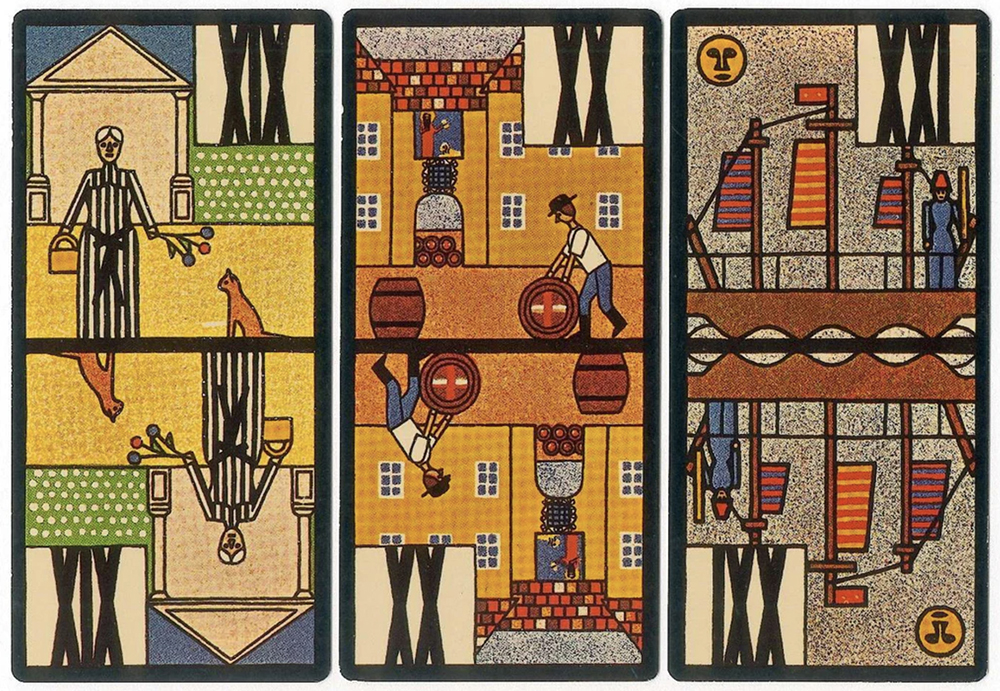

Jugendstil Tarot deck designed by Edith Moser

Jugendstil Tarot deck designed by Edith MoserEdith Moser’s history is obscure because her work was not recorded, and few examples survive. She studied at the Academy for Applied Arts in Vienna as a guest student under Josef Hoffmann until 1905, when she married. The tarot cards she designed were initially produced for the Wiener Werkstätte in the aesthetic for which it is recognized: straight lines and simple forms. Each card depicts events from the Moser family life, combining imagery of wooden toy soldiers with biblical and mythological themes. A common motif for her work was depictions of her family, most likely because childcare and domestic tasks were historically women’s domains.

It is possible that Moser was exploring esoteric traditions in creating the cards. However, documentation of women’s spiritualism in design is limited, so understanding how these designers engage in this practice can take several forms. Many women were involved in spiritual practice because it provided “social space for experimentation in alternative theologies, gender roles, sexual relations, and leadership structures” (Asprem 71). Experimental spaces like these furnished opportunities for women in design to create self-initiated work. Moreover, designers could accommodate spiritual practices in the home through the tarot decks they created. Finally, Theosophy promoted women’s education and employment outside the home, thereby supporting women with the professional skills provided by newly established art and design schools.

Pamela Colman Smith, an American born in London, designed in 1909 what was commonly known as the Rider-Waite Tarot deck, but now credits her involvement. Unlike Moser, Smith was extensively involved in Western esoteric practices as a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, founded in 1888. This group, which combined elements of Freemasonry and reinvented medieval sects such as the Knights Templar, was secret and invite-only. The Golden Dawn can claim to have invented modern occultism, and “women were held up as equals and could hold leadership positions” (Owen 17). Smith met the English author Arthur Edward Waite (1857–1942) as a member of the London-based, Isis-Urania temple of the Order led by the writer William Butler Yeats. Waite, a scholarly mystic who wrote extensively on occult and esoteric matters, discovered a group of manuscripts on tarot and felt he could assemble a more meaningful collection that included images. He also sought to create an instrument that embodied the “secret tradition” of Western Christian mysticism, an idea he emphasized strongly in his writing (Waite).

With her first-hand knowledge of the “secret tradition” and her education at Pratt Institute, Smith was hired as a freelance designer to execute the cards. Most documentation of the deck's process records Waite’s insistence on art-directing Smith for the Major Arcana. Moreover, Waite dismisses her interest in the deeper meanings of the mysteries of the deck and her need for “guidance” (Kaplan 75). However, when it came time to design the Minor Arcana, Waite had lost interest in art directing. Smith claimed creative license, evident in the composition’s theatrical qualities, which were a passion of hers. She drew inspiration from her beliefs in gender fluidity and equality—using her female friends as models for traditionally male roles. Additionally, the cards’ compositions, which embed allegorical signs and symbols, reflect her interest in authorship and Catholic traditions. Smith was fully capable of realizing the 56 additional cards, having run a women-focused Green Sheaf Press from 1903 to 1904, which she founded after she experienced the male-dominated publishing world.

Minor Arcana Cards | Rider-Waite-Smith Deck

Minor Arcana Cards | Rider-Waite-Smith DeckSmith and Waite did not consider their creation a significant achievement, even though the deck became prototypical of the later twentieth and twenty-first century cards. “Most ‘new’ decks are either annotative insofar as they maintain the general Rider-Waite-Smith appearance and aesthetic, or discursive insofar as they maintain that deck's structure and general associations but also integrate one or more literary works, mythologies, and cultures" (Auger 11). Shortly after completing the project, Smith converted to Catholicism and “kept her Golden Dawn vow of secrecy, never discussing anything about the possible meaning in her cards” (Kaplan 353). For many years, the designer of this iconic deck had largely been forgotten because the cards were named after Waite and the printer, William Rider & Son. Smith’s serpentine signature embedded into each composition was the only clue to her contribution. There is no record of her fee for the project, but we know she experienced financial difficulties and struggled to find employment for much of her life. Only recently has she been more widely credited for her contributions to this iconic work.

Produced almost 30 years after the Rider-Waite-Smith Deck, the Thoth Tarot, or Aleister Crowley deck as it is sometimes known, was created during WWII, published in 1969, and commercially available in 1977, after both creators, Aleister Crowley (1875–1947) and Lady Frieda Harris, had died. Crowley was a quirky English occultist, writer, and mystic; he was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the founder of the religion Thelema, which he led as the prophet. Harris was the wife of a wealthy baronet who worked as an illustrator. Not much has been recorded about her educational history, whether she was self-taught, but it is known that she was not involved in Western esoteric practice until she met Crowley.

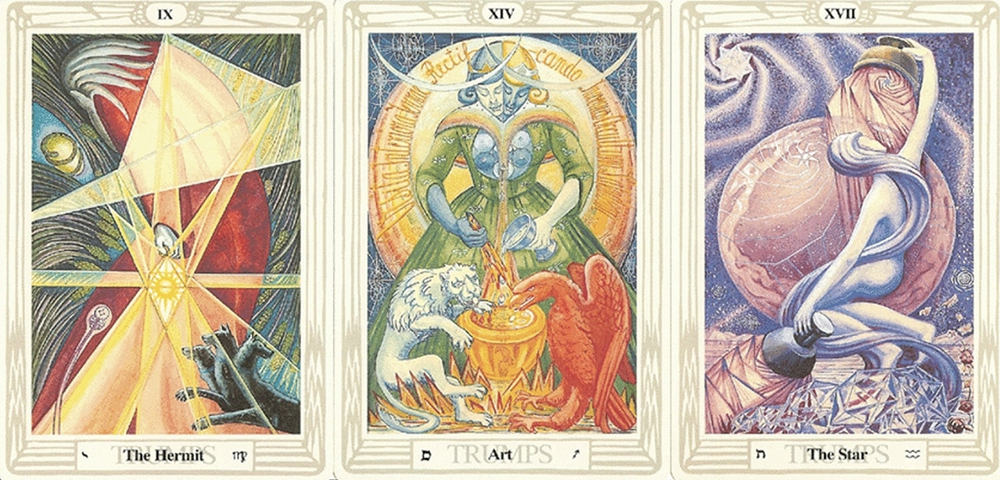

Thoth Tarot Deck

Thoth Tarot DeckIn 1937, Crowley initiated a tarot card project in tribute to the Ancient Egyptian god of wisdom, Thoth. An articulation for Crowley that “corresponds with such ancient representations of mystical and esoteric beliefs lending credence to the view that the Tarot originated as another such system rather than an aristocratic game” (Auger 11). After a successful meeting, Harris was invited to visualize Crowley’s ideas. Within their partnership, he encouraged her to study Western esoteric practices. She read Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy, a critical text for the deck's creation; she became an active Co-Mason in the branch founded by Madame Blavatsky

and used the divination practice of I Ching. According to Crowley's unpublished Society of Hidden Masters, Lady Harris became his “disciple.” Waite held similar sentiments, and, like Smith, Harris profoundly shaped the deck, not simply carrying out his direction but also incorporating her own occult, magical, spiritual, and scientific views into the project. The visual language of the deck is derived from art deco aesthetics and Harris’s knowledge of Egyptian, Kabbalistic, Christian, and astrological symbols. During her initiation, Harris also studied projective synthetic geometry, as reflected in Steiner’s teachings, and this became a common motif in the cards. Crowley later said that Harris devoted her genius to this work. Not only did Harris devote her artistic genius and spiritual knowledge, but she also funded and managed the project until completion. Without this effort, the cards would never have been made.

The two women, Smith and Harris, were hired to produce two tarot projects initiated by men who had the agency to do so. Nevertheless, these women demonstrated that they did not treat the tarot projects as mere commissions but sought authority over the work through their education, craft, and financial support.

Contemporary Practice

As a spiritual practice and ritual tool, tarot is distinct from other religious expressions because it affords each generation the latitude to reinterpret it individually. Designers carry forward the tenacity and motifs established by Moser, Smith, and Harris in their work. Courtney Alexander, a multi-media artist who self-described as “a person who lives at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities as a fat black queer femme” (Alexander), created the Dust II Onyx: A Melanated Tarot, a self-commissioned deck. With a practitioner’s history in Western esotericism, she created discursive cards from the Rider-Waite-Smith deck featuring cultural myths, symbolism, history, and icons within the Black Diaspora. Isa Beniston started her Gentle Thrills Tarot deck during the global Covid-19 pandemic, incorporating colorful graphic compositions rooted in traditional tarot archetypes. Also, in keeping with the symbology and geometric figures in the Rider-Waite-Smith cards, is the Dreslyn Tarot deck, designed by Kati Forner. The cards were commissioned for a fashion store of the same name, and the minimalist compositions, consisting of black-and-white outlined symbols, starkly contrast with heavily illustrated decks. With its enigmatic quality, tarot offers these contemporary designers a means to explore their reality and the phenomenological mysteries of existence and consciousness. Our longing for meaning, purpose, and a connection to others is a timeless universality that the cards offer.

Conclusion

In this history, spiritual practice and design provide a form of agency, a means to claim power and employ voice. What is important to note is that the resounding ‘voice’ is not that of individual women but a collective. Illuminating these practitioners’ work—designers and spiritual practitioners alike—requires a complex, “messy” history that examines how social phenomena, behaviors, or circumstances arose and how they affected individuals, communities, and the social fabric. There is a growing recognition in the arts of the significance of our sacred beliefs that have shaped popular culture and artistic works. However, design history has largely discarded research on this topic. Narratives like this seek to enrich history, advancing ideological continuation so those who engage in the ritual or create tarot decks can carry on ‘wisdom’ traditions embedded within this occult practice. Today women’s opportunities are far more divergent, abundant, and socially accepted than our historical counterparts due to their collective effort. Tarot card designers and their audiences should be aware of their deck's lineage and women's critical role in their creation and in advancing women’s equality.

WORKS CITED

Alexander, Courtney. "About the Artist." Courtney Alexander Portfolio, 16 May 2023, courtneyalexander.art/bio#:~:text=Courtney%20Alexander%20is%20a%20multimedia,a%20fat%20black%20queer%20femme. Accessed 16 May 2023.

Auger, Emily E. Tarot and Other Meditation Decks: History, Theory, Aesthetics, Typology. Jefferson: McFarland, 2004.

Asprem, Egil, et al. Hermes Explains : Thirty Questions About Western Esotericism. Amsterdam University Press, 2019.

Bressler, Ann Lee. The Universalist Movement in America, 1770-1880. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Buckley, Cheryl. “Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design.” Design Issues, vol. 3, no. 2, 1986, pp. 3–14. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1511480. Accessed 5 May 2023.

Calvino, Italo. The Castle of Crossed Destinies. 1st ed., Mariner Books Classics, 1979.

Gecewicz, Clair. "‘New Age’ Beliefs Common among Both Religious and Nonreligious Americans." Pew Research Center, 1 Oct. 2018, www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/10/01/new-age-beliefs-common-among-both-religious-and-nonreligious-americans/. Accessed 3 May 2023.

Goodman, Helen. “Women Illustrators of the Golden Age of American Illustration.” Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 8, no. 1, 1987, pp. 13–22. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1358335. Accessed 5 May 2023.

Hunt, Elle. "When the Mystical Goes Mainstream: How Tarot Became a Self-care Phenomenon." Guardian News & Media, 27 Oct. 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/oct/27/tarot-cards-self-care-jessica-dore-interview Accessed 4 May 2023.

Kaplan, Stuart R., et al. Pamela Colman Smith : the Untold Story. First edition., U.S. Games Systems, Inc., 2018.

Owen, Alex, 'The Sorcerer and His Apprentice: Aleister Crowley and the Magical Exploration of Edwardian Subjectivity', in Henrik Bogdan, and Martin P. Starr (eds), Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism (New York, 2012; online edn, Oxford Academic, 24 Jan. 2013), https://doi-org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199863075.003.0002, accessed 7 May 2023.

Ross, Alex. "The Occult Roots of Modernism." The New Yorker, 19 Jun. 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/06/26/the-occult-roots-of-modernism, accessed 7 May 2023.

Scotford, Martha., 'Messy History vs. Neat History: Toward an Expanded View of Women in Graphic Design,’ in A. Blauvelt (ed.), New Perspectives: Critical Histories of Graphic Design, Visible Language (1994) 28.4 pp. 367-87.

Sosteric, Mike. “A Sociology of Tarot.” The Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie, vol. 39, no. 3, 2014, pp. 357–92. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/canajsocicahican.39.3.357. Accessed 6 May 2023.

Thomson, Ellen Mazur. “Alms for Oblivion: The History of Women in Early American Graphic Design.” Design Issues, vol. 10, no. 2, 1994, pp. 27–48. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1511627. Accessed 5 May 2023.

Waite, Arthur Edward, and Julio Mario Santo Domingo Collection. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot : Being Fragments of a Secret Tradition Under the Veil of Divination. 2nd ed., 1971., Rider, 1971.

Walls. Nina de Angeli. “Educating Women for Art and Commerce: The Philadelphia School of Design, 1848-1932.” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 3, 1994, pp. 329–55. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/369956. Accessed 5 May 2023.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bogdan, Henrik., and Martin P. Starr. Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism : an Anthology of Critical Studies. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Brandow-Faller, Megan. The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy. 1st ed., Penn State University Press, 2020.

Buchanan, Richard, et al. “Design.” Educational Technology, vol. 53, no. 5, 2013, pp. 25–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44430183. Accessed 6 May 2023.

Carson, Fiona, and Claire Pajaczkowska, editors. Feminist Visual Culture. Edinburgh University Press, 2000.

Crowley, Aleister, et al. The Book of Thoth; a Short Essay on the Tarot of the Egyptians, Being the Equinox, Volume III, No. 5. S. Weiser, 1969.

Faivre, Antoine, and Christine. Rhone. Western Esotericism :a Concise History. State University of New York (SUNY) Press, 2010.

Faxneld, Per, 'Theosophical Luciferianism and Feminist Celebrations of Eve,’ Satanic Feminism: Lucifer as the Liberator of Woman in Nineteenth-Century Culture. New York, 2017; online edn, Oxford Academic, 2017.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. Western Esotericism : a Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J., et al. Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism. Brill, 2005.

LeMieux, David., and Julio Mario Santo Domingo Collection. The Ancient Tarot and Its Symbolism : a Guide to the Secret Keys of the Tarot Cards. Cornwall Books, 1985.

Rosenman, Robert. "ART NOUVEAU MAGAZINES." Vienna Secession: Art Nouveau in Vienna and Germany 1895-1918, 2 Feb. 2017, www.theviennasecession.com/art-nouveau-magazines/. Accessed 5 Apr. 2023.

Sykes, Ruth. "Recognizing the Women Designers Lost to History Will Take Work—We Should Do It Collectively." AIGA Eye on Design, 8 May 2019, eyeondesign.aiga.org/we-should-work-to-recognize-the-women-designers-who-never-got-their-due/. Accessed 3 May 2023.

Thomson, Ellen Mazur. The Origins of Graphic Design in America, 1870-1920. Yale University Press, 1997.

Warlick, M. E. “Mythic Rebirth in Gustav Klimt’s Stoclet Frieze: New Considerations of Its Egyptianizing Form and Content.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 74, no. 1, 1992, pp. 115–34. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3045853. Accessed 29 Apr. 2023.